Bewitched Rye and a Spooky Seasonal Recipe

Something’s Rotten in the Massachusetts Bay Colony: how contaminated grains may have influenced the Salem Witch Trials

By Molly Haas, MS, RD, CD, CNSC

Most dietitians think about food and nutrition, even when we’re off the clock. This could explain why on a recent trip to Salem, Massachusetts, I was not content to simply visit the exterior filming locations of Hocus Pocus and pay too much for witchy souvenirs (I did both things). I also wanted to research the theory that the Salem Witch Trials might have been caused – or at least heavily influenced – by the effects of ergot poisoning. Come with me on this journey…

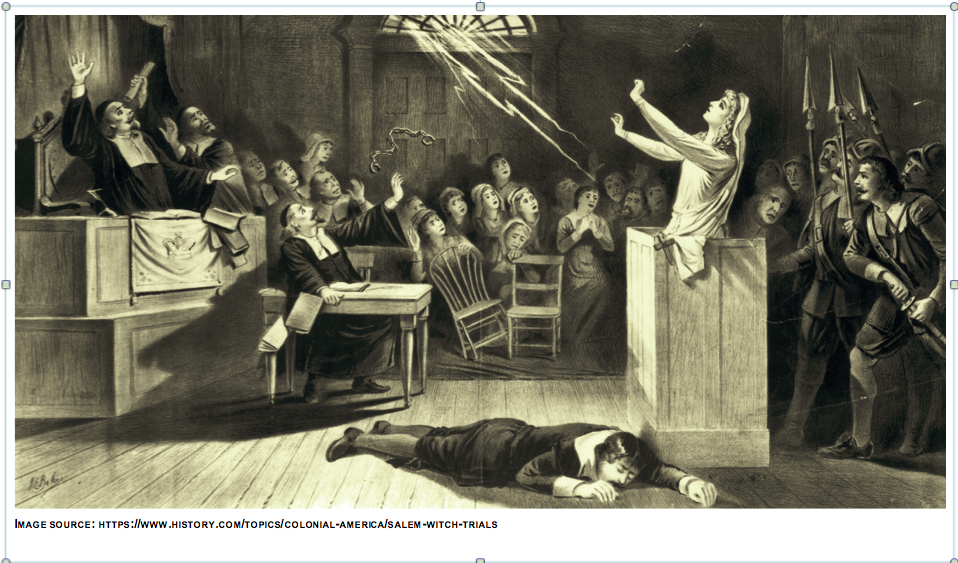

In February 1692, a small group of girls in Salem Village began exhibiting unexplained behavior such as violent bodily contortions, odd vocalizations, and hallucinations. Their bodies were plagued with pins and needles sensations, and they became intermittently catatonic. When taken to the local doctor, the girls were diagnosed as “bewitched.” Meaning, someone in the town must have cast a spell on the innocent girls. While accusations of witchcraft were not a common occurrence in Puritan society, they did believe in witches and took these accusations seriously. One of the afflicted girls, Betty Parris, was the town pastor’s daughter, giving further credence to the notion that the devil was at work in Salem. The girls were pressed to name their tormentors, and in 16 months, over 200 individuals were accused of practicing witchcraft. The accusations levied upon individuals were likely due to a combination of many economic and political factors. But one interesting theory has emerged to explain some of the bizarre behavior exhibited by the “afflicted.”

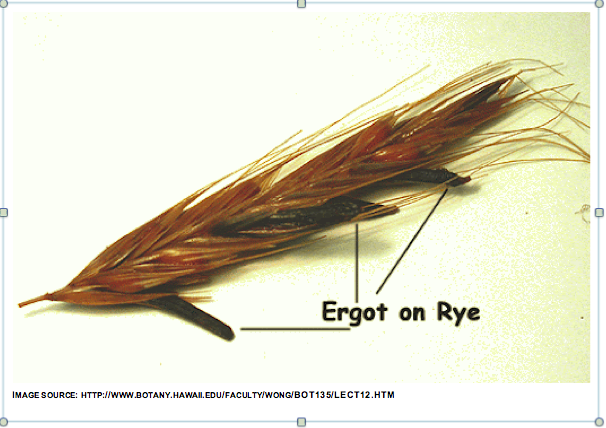

In 1976, behavioral psychologist Linnda Caporael wrote an article for the journal Science suggesting that the symptoms of bewitching closely resemble that of ergotism. Ergotism is the condition caused by the fungus Claviceps purpurea, which can contaminate cereal grains. Rye is particularly susceptible to contamination and was the staple crop in Salem at the time. Fungal spores invade the grains and turn affected kernels purplish-black, which can be mistaken as larger and darker grains of rye. C. purpurea thrives in a warm, damp environment. By reviewing journals of Salem residents, Caporael determined the spring and summer of 1691 would’ve produced just such conditions. In contrast, the following summer was dry, possibly explaining why the mass hysteria ended abruptly in 1693.

Ergotism is in part characterized by muscle spasms, vomiting, delusions, hallucinations, and a crawling sensation on the skin. In fact, one of the byproducts of ergot contamination is lysergic acid, used to make LSD. The symptoms of ergotism are strikingly similar to witness accounts of the afflicted girls’ odd behavior. Caporael noted that most of the accusers lived near one another on the side of Salem Village with the swampiest, wettest conditions.

The cause of ergotism was identified in 1695, shortly after the mass hysteria of Salem concluded. Public health and agricultural measures taken in the early 1800s have kept cases of ergotism rare and localized. Although there is no way to definitively determine whether ergot played a part in the Salem Witch Trials, it is a fascinating theory (albeit, a controversial one) and a story to tell friends and family when they ask why you’re such a stickler for food safety.

The hysteria of the Salem Witch Trials claimed the lives of 25 individuals. There is no amount of kitschy witch imagery and overpriced “haunted” tours that can cover up that what happened over 300 years ago was needless and tragic. If your travels take you to Salem, I recommend doing your own research into the history of the infamous Witch Trials. Wicked Good Books has a section dedicated to books written on the subject (while you’re at it, grab a coffee at the nearby Brew Box at 131 Essex St). And don’t forget to eat a lobster roll while you’re there. You know, for research.

Finally, if you would like to try your hand with some (non contaminated) rye, make Boston brown bread which has roots in 17th century New England. And if you want to see how recipes were written back then, here’s one from The Compleat Cook’s Guide from 1683. It’s cryptic, much like a technical challenge on the Great British Bake Off, and no pictures exist because I’m not sure anyone has attempted to make it, let alone photograph their efforts. Good luck following along, should you choose to grace your holiday table with some Puritan fare:

To Make a Hedg-hog Pudding (reprinted from What Salem Dames Cooked in 1700, 1800, and 1900)*

Put some raisins of the sun into a deep wooden dish, and then take some grated bread, one pint of sweet cream, three yolks of eggs, with two of the whites, and some beef suet, grated nutmeg, and salt, then sweeten it with sugar, and temper it all well together, and so lay it into the dish upon the raisins, then tie a cloth about the dish and boil it in beef broth and when you take it up lay it in a pewter dish, with the raisins uppermost, and then stick blanched almonds very thick upon the pudding, then strew some sugar about the dish, and serve it.

*No real hedgehogs were harmed in the making of hedg-hog pudding.

Resources:

The Board of Managers of the Esther C. Mack Industrial School of Salem, MA. (1910). What Salem dames cooked: Being a choice collection of recipes wherein is shewn how the delectable practice of the salem Dames from the year 1683, to 1730, until 1800 and 1900, may be restored with pleasure to those desirous of experiencing the delights of their cookery: Together with a few housekeeping hints and numerous appropriate quotations. The Stetson Press of Boston.

Hill, F. (2002). A delusion of Satan: The full story of the Salem witch trials. Da Capo.

Public Broadcasting Service. (2019, April 12). The witches curse ~ clues and evidence. PBS. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/witches-curse-clues-evidence/1501/.

Hagan, A. (2018, November 2). From poisoning to pharmacy: A tale of Two ergots. ASM.org. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://asm.org/Articles/2018/November/From-Poisoning-to-Pharmacy-A-Tale-of-Two-Ergots.

Molly Haas, MS, RD, CD, CNSC obtained a Master’s of Science from the University of Washington School of Public Health in 2017 and now works as an inpatient clinical dietitian at Swedish Medical Center – First Hill. Contrary to what this blog post may lead you to believe, she does not regularly bore her coworkers with historical conspiracy theories and instead has a very active social life and totally normal hobbies. Molly lives in the South Beacon Hill neighborhood of Seattle with her husband and their pit bull, Betty.